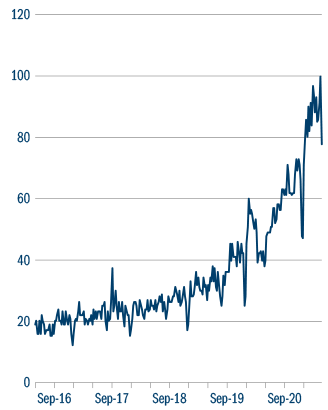

Responsible Investment has witnessed

strong growth over the past five years.

However, the past six months have seen

it embark on a much steeper trajectory.

If we take a Google Analytics view

on worldwide searches for “ESG”

(environmental, social and governance)

phrases, it peaked in March 2021 (Figure 1).

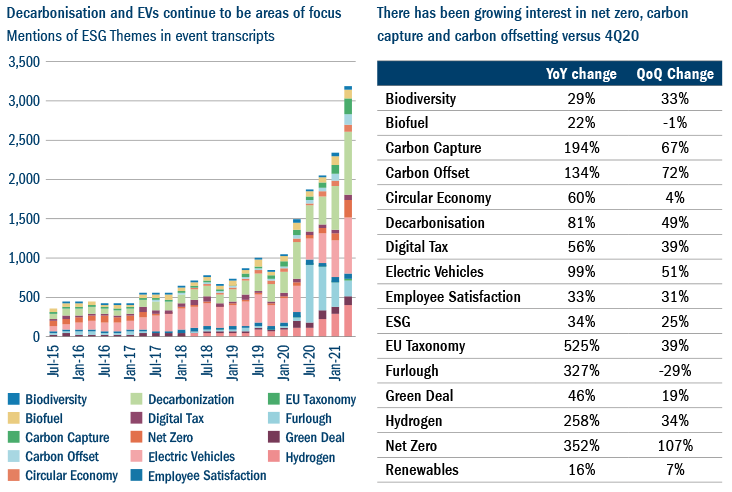

This growth is also evident within corporate

transcripts with respect to the growing

usage of ESG themes (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Google Analytics returns for ESG phrases

Source: Google Analytics, May 2021. Numbers represent search

interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given

region and time. A value of 100 is peak popularity. A value of

50 means the term is half as popular. A zero means there was

insufficient data for this item.

Figure 2: Key RI themes increasingly mentioned in company transcripts

Source: Alphasense (left) and Morgan Stanley (right), as at April 2021.

One of the enablers of this stellar growth has been strong policy support, particularly in Europe. The build out of

green infrastructure here is nothing if not ambitious. The European Union was among the first to commit to carbon neutrality – by 20501 – and has

gone furthest in publishing investment plans to enable a green transition. Some observers estimate that up to

€7 trillion in infrastructure spending will be required over the next 30 years to achieve

the EU’s stated goals, of which around €3 trillion will come from private sources.2

But while 2050 may seem a distant

prospect, the EU does not plan to start

its transformation slowly. The Green Deal,

which is the cornerstone of the continent’s

transition to a low-carbon future, aims

to deliver a reduction of 50%-55% in

carbon emissions by 2030 compared with

1990 levels.3 This will not be achieved

through new projects alone, developing

existing brownfield projects will be key

to supporting sustainable investment.

For investors, Europe’s gargantuan appetite

for green infrastructure investment will

inevitably lead to significant investment

opportunities. The Green Deal’s targets

imply an investment gap of around

€470 billion a year through to 2030.4

This will not be bridged without major

injections of private capital alongside state

spending and incentives, creating huge,

multi-year investment opportunities.

Aside from environmental benefits,

green infrastructure investment can also

accrue economic advantages through

the stimulation of economic activity –

a recent IMF5 paper concluded that every

dollar spent on carbon-neutral activities

generates more than a dollar of

economic activity, with this positive

multiplier effect persisting for at least

four years and the impact on economic

activity being two to seven times

larger than those associated with

environmentally detrimental measures.

Policies driving transformation

As Europe gears up to stimulate economic

recovery from Covid-19, so its plans

for green infrastructure investment

have increased. Joining forces with

the Green Deal, the EU Recovery Plan

gives climate transition a central role in

the continent’s blueprint for economic

recovery and growth, aiming to create

the jobs of the future as well as positive

climate and sustainability impacts,

including reduced emissions, greater

energy self-sufficiency and lower bills.

To support its Green Deal agenda, the

EU originally intended to mobilise at least

€1 trillion of public and private investment

by 2030, but the stimulus package drawn

up to address the economic impact

of Covid-19 has boosted this. The EU

Recovery Plan’s additional stimulus for

the period 2021-27 is expected to total

around €1.85 trillion, roughly a quarter

of which could be allocated to climate

transition-related investments.6 Additionally,

a €17.5 billion Just Transition Fund has

been agreed as part of the Green Deal to

mitigate the economic and employment

impacts of Europe’s climate transition.7

The EU’s Green Taxonomy will help

to drive private investment into green

infrastructure. This is an ambitious

attempt to classify economic activities

according to their sustainability, and is

intended to influence the way private

capital is allocated, alongside the less

prescriptive framework of the 17 UN

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Globally, the effort to achieve the SDGs

could create more than $12 trillion in

market opportunities8 across four key

areas – health and wellbeing, cities, energy

and materials and food and agriculture.

"For investors, Europe’s gargantuan appetite for green infrastructure investment will inevitably lead to significant investment opportunities"

1. Renewable energy

The plan calls for a doubling of electricity generation from renewable sources by 2030 to help meet its emissions reduction targets. This implies a major increase in European utility companies’ current rates of investment in renewable capacity and power grids. According to research carried out by the consultancy AT Kearney, annual renewables investment in Europe will rise from €60 billion in 2020 to €90 billion in 2022. By 2030, investment in European wind and solar capacity will total at least €650 billion and could reach €1 trillion.9 This is likely to boost utility valuations in Europe significantly, particularly given the big increase in demand that will result from the replacement of fossil fuels with electricity in transportation. It will also flow through to rising profits at equipment makers such as Danish turbine maker Vestas, which reported return on capital employed last year of around 20%.10

The plan calls for a doubling of electricity generation from renewable sources by 2030 to help meet its emissions reduction targets. This implies a major increase in European utility companies’ current rates of investment in renewable capacity and power grids. According to research carried out by the consultancy AT Kearney, annual renewables investment in Europe will rise from €60 billion in 2020 to €90 billion in 2022. By 2030, investment in European wind and solar capacity will total at least €650 billion and could reach €1 trillion.9 This is likely to boost utility valuations in Europe significantly, particularly given the big increase in demand that will result from the replacement of fossil fuels with electricity in transportation. It will also flow through to rising profits at equipment makers such as Danish turbine maker Vestas, which reported return on capital employed last year of around 20%.10

2. Green mobility

The transition to electric power for transport is a central element of the Green Deal, which stipulates that by 2030 at least 30 million zero-emission cars will be in use on Europe’s roads,11 high-speed rail travel will double across Europe and all scheduled mass transport for journeys of less than 500km should be carbon-neutral.12

The transition to electric power for transport is a central element of the Green Deal, which stipulates that by 2030 at least 30 million zero-emission cars will be in use on Europe’s roads,11 high-speed rail travel will double across Europe and all scheduled mass transport for journeys of less than 500km should be carbon-neutral.12

For some companies, these targets

present immediate opportunities to

generate attractive returns. Rail equipment

makers are well positioned to benefit from

the Green Deal, although an accelerated

transition to electric vehicles will pose

major challenges for automakers that

need to develop new vehicles and ensure

access to sufficient battery capacity.

3. Hydrogen as a future energy source

There is growing interest in hydrogen as a clean energy source, although it remains expensive relative to others. The cost of so-called “green hydrogen” – made using renewable electricity to power electrolysis of water – has fallen thanks to dramatically cheaper renewable energy, but remains seven times higher than fossil fuels. Hydrogen is also difficult to store and transport.13 However, it has major potential in areas where electrification is not feasible, such as heavy industry, trucks, shipping and seasonal energy storage, and the EU aims to grow the share of hydrogen in the bloc’s energy mix from less than 2% currently to 13%- 14% by 2050.14 To realise this potential, major policy support will be necessary to encourage investment. The European Commission estimates the carbon price under the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme will need to rise from around €30 currently to €55-€90 a tonne.15 Examples of projects getting underway include Ørsted building a 1GW green hydrogen plant in the Dutch North Sea, which is slated for operations by 2030;16 and in the UK Cadent’s HyNet North West project, which has been awarded £72 million in funding, partly from the UK government, to finance a hydrogen carbon capture and storage (CCS) project. It is hoped the fresh capital will accelerate the project to a final investment decision by 2023 in order for the initial phase to become operational by 2025.17

There is growing interest in hydrogen as a clean energy source, although it remains expensive relative to others. The cost of so-called “green hydrogen” – made using renewable electricity to power electrolysis of water – has fallen thanks to dramatically cheaper renewable energy, but remains seven times higher than fossil fuels. Hydrogen is also difficult to store and transport.13 However, it has major potential in areas where electrification is not feasible, such as heavy industry, trucks, shipping and seasonal energy storage, and the EU aims to grow the share of hydrogen in the bloc’s energy mix from less than 2% currently to 13%- 14% by 2050.14 To realise this potential, major policy support will be necessary to encourage investment. The European Commission estimates the carbon price under the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme will need to rise from around €30 currently to €55-€90 a tonne.15 Examples of projects getting underway include Ørsted building a 1GW green hydrogen plant in the Dutch North Sea, which is slated for operations by 2030;16 and in the UK Cadent’s HyNet North West project, which has been awarded £72 million in funding, partly from the UK government, to finance a hydrogen carbon capture and storage (CCS) project. It is hoped the fresh capital will accelerate the project to a final investment decision by 2023 in order for the initial phase to become operational by 2025.17

4. Building stock

Around three-quarters of the 220 million buildings in the EU are deemed energy inefficient.18 The EU’s Covid-19 recovery plan will channel major investment into upgrading them, given that buildings account for 36% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions and 40% of energy consumption. The plan’s key targets call for a 60% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from buildings by 2030 and a cut in energy used for heating and cooling of 18%. To achieve this it aims to double the renovation rate of buildings to 2% over the next decade, which will require investment of €275 billion a year. Energy efficiency standards will also be tightened.19

Around three-quarters of the 220 million buildings in the EU are deemed energy inefficient.18 The EU’s Covid-19 recovery plan will channel major investment into upgrading them, given that buildings account for 36% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions and 40% of energy consumption. The plan’s key targets call for a 60% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from buildings by 2030 and a cut in energy used for heating and cooling of 18%. To achieve this it aims to double the renovation rate of buildings to 2% over the next decade, which will require investment of €275 billion a year. Energy efficiency standards will also be tightened.19

These themes are consistent with

the opportunities we are seeing in

the infrastructure space, in particular

in the past 12 months those themes

linked to methods of decarbonisation

such as carbon capture, and solutions

around decarbonsiation (both

brownfield and greenfield), namely

hydrogen and carbon offsetting.

Thus, the supportive policy backdrop

is presenting sustainability-focused

openings within the small mid-cap nexus.

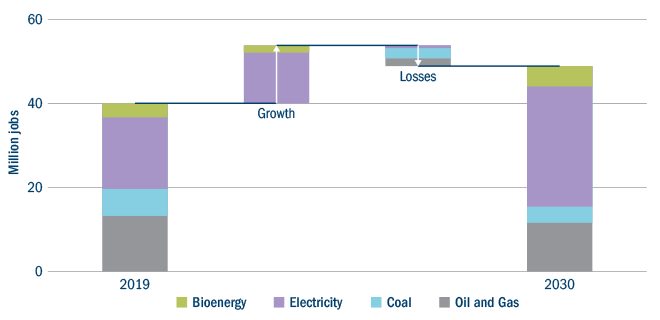

Don’t forget social!

This rapid move towards net zero

creates a risk that some people are

left behind – perhaps those without the

opportunity to reskill into low-carbon

industries or unable to access the

benefits of the new energy system.

The Just Transition acknowledges the

social implications of delivering net

zero, from jobs and training to working

with communities and ensuring no

one is left behind (Figure 3). Working

with our portfolio companies – and any

future ones – to ensure we create a

just transition for employees is of the

utmost importance, and strategies to

ensure positive social outcomes are

embedded in our business plans.

Figure 3: Global employment in energy supply in the net-zero pathway, 2019-2030

Source: International Energy Agency, 2019.

Looking forward, Europe’s drive to

green its economy will lead to a new

range of opportunities in infrastructure

investment. Indeed, Europe’s policymakers

are aware that they cannot achieve their

zero-carbon goals without attracting

private investment. Given the Green

Deal’s ambitious timeline over the

next 10 years, now is the time to be

exploring the major investment themes.